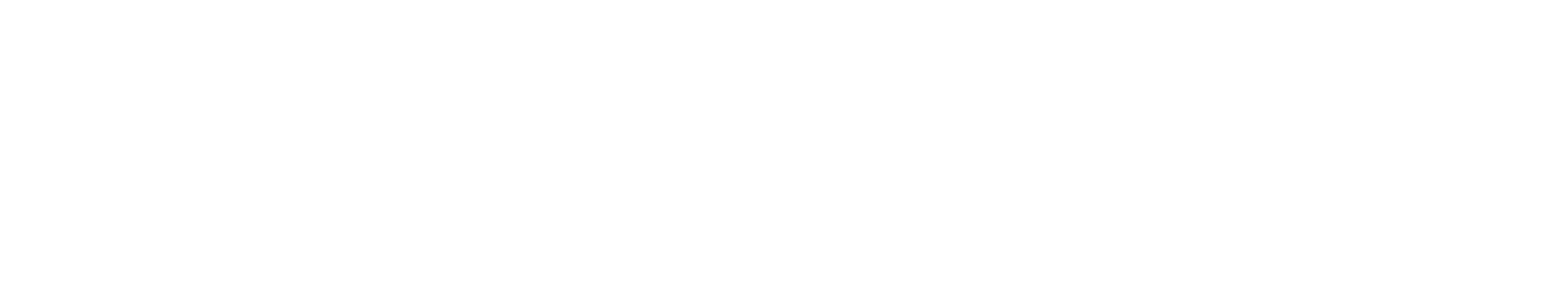

For 12 years, Francis was the pastor of the Church, an Argentine Pope who brought the best of the Latin American Church to the Vatican: its simplicity, its spirituality, its ever-expanding attitude, and its commitment to being with the least. A Pope with a firm and strong voice, yet who knew how to communicate tenderly and without confrontation, humble and frank, full of gestures and surprises, who grew older, but who steered the ship of Peter with the strength of one who allows himself to be moved by the Holy Spirit. We invite you to read the following Humanitas magazine editorial team article.

A world leader who was listened to and respected at a time when the world was engulfed by the senseless cruelty of war and the urgent need to confront environmental degradation. Within the Church, he had to courageously confront the earthquake of sexual abuse, firmly condemning, decisively reforming, and asking for forgiveness with pain and shame.

These years brought meetings, trips, writings, and gestures laden with symbolism. There were moments of mass celebration and solitude, such as the blessing given in the middle of a rainy St. Peter’s Square, where he prayed for the victims of the coronavirus at the pandemic's most challenging moment.

Francis was the Pope of mercy, the Pope of synodality, and the Pope of the Church in motion. Under him, themes such as urgent ecclesial renewal, the Church’s missionary vocation, interreligious dialogue, the current role of women in society, and sustainability gained special relevance. Rather than condemning, he passionately and convincingly highlighted the beauty of the Christian experience and tirelessly encouraged all Catholic communities worldwide to live the joy of the Faith.

1. Living with a Pope Emeritus

For the first time in history, a Pope had to live a few hundred meters away from a Pope Emeritus for over a decade. It was a new, unprecedented relationship, and from the beginning, it might generate some tension, power struggles, or doubts about the legitimacy of the newly elected Pope. The truth is, none of that happened. The relationship between the two was marked by respect, cordiality, and mutual admiration. “For me, Benedict was a father; with what delicacy he accompanied me on this journey!” [1] is how Francis describes their relationship in the first person in Javier Martínez-Brocal’s book entitled The Successor: My Memories of Benedict XVI. “I visit him frequently and come away edified by his transparent gaze. He lives in contemplation […] I admire his intelligence. He is a great man.” [2]

The two popes had already met on several occasions before Francis’s election. Bergoglio met Ratzinger first through his writings and later as the Archbishop of Buenos Aires. The two cardinals met at the 2005 conclave, where Ratzinger was elected Pope Benedict XVI. Their closest moment occurred during the General Conference of the Latin American and Caribbean Episcopate in Aparecida, Brazil, in 2007, where the vision and capacity for synthesis that Bergoglio demonstrated in drafting the Final Document caught the attention of Benedict and the other participants.

With the unprecedented resignation of Benedict XVI and the election of Francis, a new kind of relationship opened up, one that both knew how to nurture. When Francis was elected Pope, before appearing before the world, he wanted to call Benedict, who was at his residence in Castel Gandolfo. She was the first person he wished to greet. Then, addressing the faithful for the first time as Pope, he said, “Before everything, I would like to pray for our bishop emeritus, Benedict XVI. Let us all pray together for him, that the Lord may bless him and the Virgin may protect him.” These were gestures that would mark the style of this relationship.

Although Benedict’s intention after his resignation was to no longer appear in public, significant moments marked his presence in the Church as Pope Emeritus. The first was the publication of the only encyclical in history written “jointly” by two Popes, Lumen Fidei (The Light of Faith). Then, in 2014, the Vatican experienced a historic day marked by the presence of four popes: two who would be elevated to the altar, John XXIII and John Paul II, and two concelebrating popes. Another significant moment was in 2016 when Francis wanted to celebrate the 65th anniversary of Benedict’s priestly ordination. On that occasion, Benedict tearfully confessed to Francis: “More than the Vatican gardens, with their beauty, their goodness is the place where I live: I feel protected.” The last public meeting between the two was reported after the 2022 consistory, a few months before Benedict’s death.

Both had very different pontificates, no doubt, but, as Massimo Borghesi points out in the introduction to his book Jorge Mario Bergoglio: An Intellectual Biography, “we are faced with a diversity of styles and accents, not of content.” The missionary Pope and the philosopher Pope each contributed, with their style, to make the beauty of the Faith shine forth.

2. Encyclicals and Important Documents

The Pope wrote four encyclicals and other significant documents, including letters, exhortations, and messages, which collectively constitute the entirety of his teaching. The first encyclical, Lumen Fidei, was published in June 2013, the first year of his pontificate. It was begun by Pope Benedict XVI and focused on the person of Christ and his grace.

A few months later, the apostolic exhortation Evangelii Gaudium was published on the proclamation of the Gospel in today’s world. Not without reason, it is considered the “roadmap” of his pontificate, for it reveals the most relevant emphasis that Francis would place on it: to be a missionary Church that, with the power of the Spirit, goes forth to the peripheries to proclaim the Gospel. In it, he presents an ecclesiology of the People of God that posits “the spiritual joy of being a people” and reclaims the role of the People of God among the peoples of the earth. He emphasizes that evangelization seeks to embrace them fraternally, growing among them, respecting their cultures and freedom, encouraging their search for truth, and recognizing the gift of mercy.

In 2015, Francis would surprise us with Laudato si’, a milestone in the Social Doctrine of the Church that points to the social and environmental consequences of lacking humanism and responsibility in the face of progress. The effort of this important magisterial document fundamentally aims to remedy this irresponsibility, the causes of which the Pope visualizes in the anthropological order. The concept of integral ecology is at the core of Laudato si’, and it understands the environment as a system of interdependent relationships between nature and the society that inhabits it, preventing us from understanding nature as something separate from society. An idea he later developed, in 2023, in the Apostolic Exhortation Laudate Deum, with the concept of “situated anthropocentrism,” affirming that human life is incomprehensible and unsustainable without other creatures.

In 2020, amid the pandemic, with Fratelli tutti, the Holy Father invited us to embark on a journey of fraternity, to be a people of brothers, to reconcile. One of the primary antecedents of the encyclical is found in the historic document on fraternity signed in February 2019 in Abu Dhabi between Francis and the Grand Imam of al-Azhar. On that occasion, the two religious leaders recognized each other as brothers and found fraternity to be the only alternative to escape the logic of confrontation that exists today. Fraternity is a message with an important social component, but above all, a political one: it also implies recognizing one another as equal citizens, as worthy of calling one another brothers. He highlights Francis of Assisi as a model of universal fraternity and social friendship.

Finally, on October 24, 2024, Pope Francis published his final encyclical, Dilexit nos, on the human and divine love of the Heart of Jesus Christ. In it, he elaborates on a profound reflection on the heart as the integrating center of the human person and a place of encounter with divine love. The encyclical reminds us that the human heart is called to a progressive transformation until it shares in the same love relationship between the Father and the Son. This sublime destiny of our souls is not mere theological speculation but a reality already being realized in our daily lives whenever we open ourselves to love and transform ourselves. With this final encyclical, the Pope wished to return to the foundation that nourishes and gives life to his entire message, which “is born from a single source, presented here in the most explicit way: Christ the Lord and His love for all humanity.” For the Pope, proper reparation to the Sacred Heart consists in uniting filial love for God with love for neighbor, where love for and of God is what gives fire, drive, and creativity to all human actions, bringing us back to the tenderness of Faith, the joy of self-giving, and the fervor of mission. From this, love springs commitment to the least because He loved them. For Francis, the love of Christ confronts us with the most fundamental dialectic: the dialectic between the great and the small, between the greatness of God and the smallness of humankind.

Other essential documents have been the exhortation Gaudete et exsultate, on the call to holiness in the contemporary world, published in March 2018, and C’est la confiance, on trust in God’s merciful love, on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of the birth of Saint Thérèse of the Child Jesus and of the Holy Face, in October 2023.

3. Apostolic Journeys

“You have to go to the periphery to see the world as it is. I always thought that one sees the world more clearly from the periphery, but in these last seven years as Pope, I have finally confirmed this. You must go to the periphery to find a new future.” [3] During his pontificate, Francis became a specialist in the peripheries. His call to reach out to others, especially the most vulnerable, became a reality through his pastoral priorities and messages, but above all, through his travels, the places he chose, and the encounters there. During his journeys, filled with gestures marked by fraternity and compassion, one could see a Gospel flourishing in distant lands. While he met with world leaders to build together a future of peace and reconciliation, he held meetings with the least of these: the poor, the imprisoned, the sick, with families, and with remote communities marked by poverty or war. He listened to testimonies, and many others could see ignored realities with him for the first time.

Francis made numerous and varied apostolic journeys, including twenty trips within Europe, fourteen to Asia, seven to Latin America and the Caribbean, four to Africa, two to North America, and one to Oceania. Some trips were for essential events for the Universal Church, such as various World Youth Days—in Brazil in 2013, Poland in 2016, Panama in 2019, and Portugal in 2023; World Meetings of Families—in the United States in 2015, Ireland in 2018, and Rome in 2022; or International Eucharistic Congresses.

In 2015, in Bangui, Central African Republic, he inaugurated the Jubilee of Mercy by opening the Holy Door in a land devastated by war. A similar, deeply symbolic gesture took place in Iraq in 2021, marking the first time a Pope visited the cradle of Christianity. There, before Christians and Muslims, he underscored the importance of interreligious dialogue for building a common future. The most extended trip of his pontificate was in 2024, when, using his wheelchair, he visited Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, East Timor, and Singapore.

Thus, with his 47 trips outside Italy, during which he visited 66 countries, Francis highlighted the multitude of colors and forms that Faith takes, recalling the universality of the Church and Christ’s desire to reach every corner of the world.

4. Combating the Culture of Abuse

Many unprecedented events demonstrate the Pope’s fight against sexual abuse committed against minors within the Church, continuing the “zero tolerance” approach developed by the last three pontiffs.

Shortly after his election, in July 2013, Francis authorized a penal reform that introduced the specific crime of “child pornography.” Then, on March 22, 2014, the Holy Father established the Pontifical Commission for the Protection of Minors, which has an advisory role. On June 4, 2016, with the Apostolic Letter in the form of a Motu Proprio entitled “As a Loving Mother,” Francis specified that among the “grave reasons” for the dismissal of a bishop, “negligence” would also be considered, particularly about cases of sexual abuse of minors and vulnerable adults. To this end, the letter details a series of procedures.

The January 2018 trip to Chile undoubtedly constituted a fundamental milestone, which led him to entrust, in February of that same year, an investigation to the Archbishop of Malta, Charles Scicluna, and Jordi Bertomeu, an official of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. The 2,300-page report revealed repeated omissions and lack of response by the Chilean Church to allegations of sexual abuse, prompting the Pope to send a letter on April 8 to the bishops of Chile, in which he expressed “pain and shame” and acknowledged having “made serious errors in the assessment and perception of the situation, especially due to a lack of truthful and balanced information.” Following the letter, he summoned the Chilean bishops to Rome to discuss the conclusions of the visit above. Before the meeting, the Pope received some of the abuse victims at the Holy See. From May 14 to 17, the 34 serving Chilean bishops went to the Vatican for three days to hear and evaluate the results. Francis presented them with a ten-page document and, on the last day, gave each of them a letter. The following day, the prelates submitted their resignations to Bergoglio in an unprecedented act. In his “Letter to the People of God on Pilgrimage in Chile” of May 31, 2018, Francis expressed his sorrow at the “atrocities,” affirming that clericalism, the closed-mindedness that lies at the root of abuses of power within the Church, must be changed.

The publication of the controversial Pennsylvania Report coincided with Francis’s trip to Ireland in August 2018 for the World Meeting of Families, with the issue of ecclesiastical abuse being a central theme of his visit. During his trip to Ireland, the Pope repeatedly expressed sorrow and shame for such abuses. He met with some victims, prayed before the Blessed Sacrament in St. Mary’s Pro-Cathedral in Dublin, and in the final ceremony of the Meeting, he replaced the Penitential Act with a request for forgiveness for sexual abuse committed by the clergy. Following this, on August 20, 2018, the Pope published a Letter from the Pope to the People of God “in response to the abuse crisis facing the Church,” in which he warned of the damage caused by the Church’s inaction and called for a renewed attitude of solidarity as a way of making history. The issue was no longer just about sexual abuse but also about the abuse of conscience and power. The text constitutes a prophetic, pastoral, and concrete document as relevant as the letter sent by Benedict XVI to the Catholics of Ireland in 2010.

Similar events have occurred in many other countries, particularly France and the United States. The Pope wrote a letter to the bishops of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops dated January 1, 2019, in which he noted that “the fight against the culture of abuse, the wound to credibility, as well as the bewilderment, confusion, and discredit in the mission demand, and demand of us, a renewed and decisive attitude to resolve the conflict.”

In February 2019, a world summit of bishops was convened on the subject. That same year, the Holy Father published the Motu Proprio Vos estis lux mundi (2019), which established stricter protocols for reporting abuse. The document was repealed and updated four years later, on March 25, 2023. The most significant change introduced in the new version of the legislation concerns “Title II,” which includes provisions regarding the responsibilities of bishops, religious superiors, and clerics charged with directing a particular Church or prelature. Many other modifications were made to align the text of the anti-abuse procedures with other normative reforms introduced between 2019 and today, in particular with the revision of the Motu Proprio Sacramentorum sanctitatis tutela (norms amended in 2021) with the amendments to Book VI of the Code of Canon Law (reform of 2021) and with the new Constitution on the Roman Curia, Praedicate Evangelium (promulgated in 2022).

5. Reform of the Roman Curia

One of the first biographies of Francis published after he was elected Pope was Austen Ivereigh’s “The Great Reformer: Francis, Portrait of a Radical Pope” (2014). The title is no coincidence; from the beginning, it was clear that Francis would decisively implement the necessary reforms to keep pace with new demands and eliminate the outdated structures of one of the most enormous bureaucracies on the planet.

For the Pope, reform primarily consisted of making the Church's structures more effective in serving its mission worldwide. Being a more missionary, sober, professional, and universal Church was one of the guiding criteria for his reforms, as expressed in his 2016 Christmas greeting. The first steps he took were taken as soon as he assumed the pontificate, constituting a Council of Cardinals to advise him on the governance of the Church and establishing a commission to study the economic and administrative affairs of the Holy See. He created new bodies, merged others, revised norms, and published new ones. But what he most insistently promoted was pastoral conversion, remembering that work in the Curia is a service that must be carried out with a spirituality of service and communion.

In 2022, he promulgated the Apostolic Constitution "Praedicate Evangelium" on the Roman Curia and its service to the Church and the world. With this document, he sought to bring greater transparency and decentralization to the Curia. It resulted from extensive collegial work, which began with the pre-conclave meetings in 2013 and involved the Council of Cardinals, as well as contributions from various churches worldwide. The new Constitution replaced Pope John Paul II’s Pastor Bonus. It confirmed a path of reform that had already been implemented almost entirely in the first years of Francis’s pontificate, through the mergers and adjustments that gave rise to new Dicasteries.

Francis’s reforms also addressed matters such as liturgical celebration and formation, as seen with the publication of the Motu Proprio Traditionis Custodes in 2021, which restricted the norms governing the use of the 1962 Missal, which had been liberalized as the “Extraordinary Roman Rite” by Benedict XVI, and with the publication of the Apostolic Letter Desiderio Desideravi in 2022, on the liturgical formation of the People of God.

Pope Francis sought to make the Curia increasingly reflect the catholicity of the Church by recruiting personnel from many countries, diverse cultures, and various states of life, including priests, deacons, men and women religious, and lay people. As never before, he promoted the service of lay men and women, instituting, for example, the lay ministry of lector and catechist.

Likewise, the appointment of new cardinals has always sought to reflect the universality of the Church, changing the composition of the College of Cardinals to one increasingly composed of cardinals from all over the world, prioritizing representatives from peripheral regions with pastoral experience and from conflict zones, and reducing the weight of those from the Roman Curia and historical sees. Today, more than 60% of the cardinal electors who will vote for the next Pope were appointed by Pope Francis.

6. Ecumenism

Ecumenism was a fundamental priority of Francis’s pontificate, as a path of encounter and collaboration around global challenges, a vision developed extensively in Fratelli tutti and Laudato Si’. The Pope expressed this in his speech in Abu Dhabi in February 2019: “Authentic dialogue requires openness, respect, and the willingness to walk together toward common goals.” Through ecumenism, Francis sought to convey a message to the world: peace can be pursued by cooperating and walking together, even if we are theologically divided. If ecumenical reconciliation exists, it is possible to aspire to reconciliation among peoples.

Many of his apostolic trips provided opportunities for exchanges with essential leaders of other religions and to jointly promote peace and understanding. He met with Patriarch Bartholomew I of the Orthodox Church of Constantinople at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem in 2014 and on the island of Lesbos in 2016, where they visited refugees. In a historic meeting, he met with Patriarch Kirill of the Russian Orthodox Church in Havana, Cuba, marking the first such encounter in nearly a thousand years. They signed a joint declaration calling for unity and cooperation.

He also held several meetings with Justin Welby, the Archbishop of Canterbury of the Anglican Church, collaborating on various peace initiatives and the fight against human trafficking. In 2023, they made an ecumenical peace pilgrimage to South Sudan. In 2016, the Pope traveled to Sweden with the Lutheran World Federation to commemorate the 500th anniversary of the Protestant Reformation.

He also delved into the relationship between the Catholic Church and Judaism. In 2014, during his apostolic journey to the Holy Land, he met with Jewish leaders and prayed at the Western Wall with Rabbi Abraham Skorka and Muslim leader Omar Abboud. In 2016, he visited Auschwitz, where he paid tribute to the victims of the Holocaust and strongly condemned antisemitism.

He also held historic meetings with leaders of the Muslim world. Ahmed el-Tayeb has met with the Grand Imam of Al-Azhar on several occasions since 2016. In 2019, they signed the Document on Human Fraternity in Abu Dhabi, a call for peace and coexistence between religions. On that occasion, he also visited the Grand Mosque of Abu Dhabi. In 2021, during his apostolic journey to Iraq, he met with Shia leader Ali al-Sistani in a historic meeting, reaffirming the commitment to peace and interreligious respect.

He participated in various ecumenical gatherings, such as the Prayer for Peace in Assisi in 2016, the World Meeting of Christian Leaders in Lund, Sweden, that same year, the Ecumenical Prayer for Creation during COP26 in Glasgow in 2021, and the Day of Prayer and Fasting for Lebanon in 2021. He also made other significant gestures, such as the announcement in 2023 that 21 Coptic martyr saints from Libya, including lay people and martyrs, had been added to the Roman Martyrology.

For Francis, ecumenism is an essential dimension of the Church’s mission. He states this in Evangelii Gaudium: “The commitment to prevailing unity among all Christians is an unavoidable path of evangelization.” [4] This call is reflected in his efforts to build bridges between divided communities and his insistence that the Christian mission must be inclusive and universal.

7. Diplomacy

Pope Francis was a staunch advocate for peace at the global level, seizing every opportunity to call for peace. He did so through his speeches, where he repeatedly reiterated, at every opportunity, in his Christmas greetings, before global leaders, and even from the hospital, that war is inhumane; through his messages, especially every January 1 for his traditional World Day of Peace message; through gestures full of symbolism, through his ecumenism; and also, above all, through the use of Vatican diplomacy, with his principal collaborator, Pietro Parolin, Secretary of State of the Holy See since 2013. This diplomacy, the oldest in the world, always sought to build bridges, facilitating peace.

Some of the most notable examples include the role he played in re-establishing diplomatic relations between Cuba and the United States in 2014 and 2015, after more than 50 years of tension. He facilitated secret dialogue between the two countries, sending letters to Barack Obama and Raúl Castro and offering the Vatican as a venue for negotiations.

The aforementioned “Document on Human Fraternity,” signed in 2019 with the Grand Imam of Al-Azhar, Ahmed el-Tayeb, in Abu Dhabi, marked a significant milestone in enhancing relations between Christians and Muslims, promoting peaceful coexistence among religions, and combating extremist violence.

In April 2019, he organized a spiritual retreat at Casa Santa Marta for the leaders of South Sudan, a country that has suffered a devastating civil war for years. At the end of the retreat, he surprised all the participants by kneeling and kissing the feet of the Sudanese leaders as a gesture of humility and a plea for peace. Later, in 2023, he visited the country with the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Moderator of the Church of Scotland, reinforcing his call for reconciliation.

In 2021, he was the first Pope to visit Iraq, a country devastated by war and religious persecution. He met with Shiite leader Ali al-Sistani, promoting interfaith dialogue and peace in the region.

Since the beginning of the conflict between Russia and Ukraine, Francis has described the war as absurd and cruel and made various calls for a ceasefire and a negotiated settlement where neither side can claim total victory. In 2023, he sent Cardinal Matteo Zuppi as a special envoy to explore avenues of dialogue between Kyiv and Moscow, as well as Washington and Beijing, a mission to which he devoted himself tirelessly. In turn, the Holy See has mediated in some prisoner exchanges. The Pope received Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky and Ukrainian religious leaders several times in the Vatican, tirelessly expressed his closeness to the Ukrainian people, and denounced the suffering of civilians and the use of war as a tool of power. While he was often criticized for not explicitly mentioning Vladimir Putin as responsible for the war, his stance has always been peaceful, diplomatic, and humanitarian.

Regarding the Israel-Palestine conflict, he has promoted peace, dialogue, and a two-state solution. In May 2014, Francis traveled to Israel, Palestine, and Jordan, meeting with leaders from both sides. Then, in a symbolic gesture, he invited Israeli President Shimon Peres and Palestinian leader Mahmoud Abbas to the Vatican for a prayer for peace. In 2015, the Vatican officially recognized Palestine as a state. Following the Hamas attack in 2023, he condemned the violence and expressed solidarity with the Israeli victims, repeatedly called for a ceasefire and an end to violence against civilians in Gaza, and criticized the humanitarian blockade while demanding the release of hostages taken by Hamas.

Another key area of Vatican diplomacy under Pope Francis has been its relationship with the Catholic Church in China, a relationship marked by various efforts at dialogue and negotiation, seeking unity between the “underground” Church (loyal to Rome) and the state-controlled Chinese Patriotic Catholic Association in a country with a growing Christian population, and also building bridges between two states estranged for more than seventy years. This issue occupied an essential place on Pope Francis’s diplomatic agenda. The most significant milestone was signing the Provisional Agreement in 2018 between the Holy See and the People’s Republic of China on the Appointment of Bishops. The first step toward restoring relations consisted of the Vatican’s recognition of the bishops appointed by the regime over the past decades and an agreement on future appointments. In return, Beijing would recognize the Pope’s authority. The agreement’s content was never made public, as it was experimental. This agreement was renewed in 2020 for a two-year term and again in 2022. Since signing the agreement, several bishops have been appointed with the recognition of both the Vatican and Beijing; however, there have also been cases of appointments without Rome’s approval, which has generated some friction. During the process, Francis has shown closeness to Catholics living in China, who have suffered persecution for years and even today continue to live under a regime that imposes restrictions on their religious practice and maintains tight control over the Church. The situation of some bishops and priests remains uncertain, with cases of surveillance and arrests. A few days after the signing of the agreement in 2018, the Pope sent a message to Chinese Catholics and the Universal Church. In 2023, during a trip to Mongolia, Francis sent a special message to Chinese Catholics.

Nicaragua also faced significant challenges under the Ortega regime. Since the 2018 social protests, when the Church welcomed injured protesters and called for national dialogue, the Ortega regime has considered many bishops, priests, and religious sisters as political enemies. Since then, a systematic campaign of harassment has unfolded. Things intensified in 2022 when the government expelled the Vatican ambassador to Nicaragua, Archbishop Waldemar Stanislaw Sommertag, and 18 members of the Missionaries of Charity. Since then, the government has carried out a severe crackdown on Catholic media, shutting down several radio stations and television channels; it closed Catholic universities, such as the Central American University, which the Jesuits had run for more than 60 years. It then revoked the legal status of the Society of Jesus of Nicaragua, confiscating its assets and transferring some private schools to its administration. The legal status of Caritas Nicaragua was also revoked, paralyzing its humanitarian work. Processions and pilgrimages were banned. Several members of the Church of Nicaragua have also been arrested, including Monsignor Rolando Álvarez, bishop of the Diocese of Matagalpa, who had served on the dialogue commission of the Nicaraguan Episcopal Conference and has become a symbol of resistance. He was sentenced to 26 years in prison in 2023 for “treason,” although he was released and deported to the Vatican in January 2024, along with other religious leaders. The Pope, although he referred to the regime as a “crude dictatorship,” avoided confrontation.

A fundamental point for understanding Francis’s position on various conflicts was his choice of a multilateral system of international relations, which seeks to end the bipolar disputes that characterize the current moment. For Francis, multilateral agreements “better guarantee than bilateral agreements the care of a truly universal common good and the protection of weaker states” [5]. Francis observed and publicly stated a growing polarization in various international forums and bodies, where a single way of thinking prevails, and new forms of colonialism emerge.

Francis always hoped that multilateralism would be a tool for building truly universal goods, such as reducing poverty, helping migrants, countering climate change, promoting nuclear disarmament, and offering humanitarian aid. However, as he affirms in Fratelli tutti, multilateralism requires courage and generosity when it comes to establishing common goals.

Francis was the Pontiff of the Universal Church and, as such, could not side solely with the West. This is even more so considering that Catholicism’s demographic center of gravity has shifted, with two-thirds of the world’s Catholics now living outside the West.

8. Synodality

During his pontificate, Francis repeatedly mentioned that synodality is a principal path in the life of the Church. This path accentuates the communion of the People of God and the presence of the Spirit at work in every member. The word Synod is composed of the preposition “sin,” which indicates “with,” and the noun “odos,” which means “way.” It thus expresses the common journey of all members of the People of God. The Pope had already experienced synodality in Latin America with the creation of CELAM and the five General Conferences of Bishops from Rio de Janeiro to Aparecida. At the same time, he often referred to the Church as the People of God, emphasizing the unity of all the faithful in a community whose sole head is Christ. With his experience in Latin America, his ecclesiology of the People of God, and drawing on the teachings of the Second Vatican Council, Francis took synodality to a new phase, maturing the awareness of the communion nature of the Church. His main collaborator on matters of synodality was Mario Grech, Secretary General of the Synod of Bishops since 2020.

In his address on the 50th anniversary of the Synod of Bishops, the Pope spoke of the synodal Church as an inverted pyramid, where the foundation of the People of God is placed at its apex and where the apex of ministry, especially of the ordained ministry, particularly the episcopal ministry, is placed at the base. He said, “In this Church, as in an inverted pyramid, the apex is below the base. For this reason, those who exercise authority are called ‘ministers’ because, according to the word’s original meaning, they are the least of all.” [6]

During his pontificate, various experiences of synodality developed at the diocesan, regional, and universal levels. The International Theological Commission promulgated the document “Synodality in the Life and Mission of the Church” in 2018. Francis led two synods on love in the family, one on young people, one on the Amazon region, and finally, to strengthen synodality, in 2021, he called the entire Church to experience, in stages, a synodal journey with a diocesan phase, a continental phase, and then concluding in the two general assemblies of the Synod of Bishops in 2023 and 2024. This journey was known as “the Synod of Synodality.” All the conclusions of that "journey" are currently being implemented, and it is expected that in 2026, the dioceses will work on developing an itinerary within their respective local churches and groups. The experience of the synodal journey in stages reflects Francis’s image of an inverted pyramid, where it is at the level of the local Church that the People of God manifest themselves in a concrete and culturally situated way. Then, there are intermediate instances of synodality between a local Church and the entire Church.

In recent years, the Church has witnessed a significant development of synodal life in different countries, regions, and continents. The German Synodal Path was the best-known, most influential, and most controversial. But synodal experiences also took place elsewhere, such as the Synodal Assembly in Madrid and other dioceses in Spain, the National Synodal Assembly of Ireland (still in progress), the Synodal Assembly of France, the National Synodal Path of Italy, the Ecclesial Assembly of Latin America and the Caribbean, and the National Plenary of Australia. In many of these instances, through processes of listening, consultation, and discernment, the sexual abuse crisis and other issues, such as the role of women in the life of the Church, pastoral renewal, ecclesial governance, and the formation of priests, were addressed.

While promoting synodality, the Pope’s primary concern was to ensure and maintain unity within the Church, considering both fundamentalist tensions, primarily from the United States, and progressive tensions, emanating from Germany. The Pope made numerous efforts to ensure that the Church could walk together, waiting for those who walked more slowly and making those who tried to get ahead wait. The abuse scandals and the responses to the crisis heightened tensions.

One of the highlights was the Pope’s relationship with the Church in Germany. This relationship was sometimes tense due to the reforms promoted by the German Synodal Path and the Vatican’s stance on specific changes in doctrine and ecclesiastical discipline. In 2019, the Pope sent a letter to the Catholics of Germany, asking that reforms be carried out in communion with the Universal Church and not independently. On several occasions, however, the Vatican has expressed concern about possible doctrinal deviations, most notably in 2022 with the letter from the Dicastery for Bishops, which warned of the impossibility of creating a permanent Synodal Council. That same year, in November, Francis summoned the German bishops to Rome for a dialogue with the Vatican, in which Cardinals Parolin, Ladaria, and Ouellet played an active role. Another critical moment was the resignation of Cardinal Reinhard Marx, one of the leaders of the German Church, in 2021; Francis rejected the resignation and asked him to continue his mission. In interviews and statements, Francis has said that the German Church risks becoming an “elite Protestant Church” if it moves away from unity with Rome.

In another area, there are the tensions the Pope has with Catholic fundamentalism, a relationship that has been strained after the publication of Amoris Laetitia in 2016 and Traditionis Custodes in 2021. Although Benedict XVI attempted to reconcile the Church with the Lefebvrists, followers of Marcel Lefebvre, who in 1988 produced a schism using the liturgy as a fundamental banner of struggle, and in 2007 granted permission to use the extraordinary form in the Mass, the Lefebvrists did not return to communion with Rome and did not recognize the validity of the reforms of Vatican II. This led Francis, with Traditionis Custodes, to ban the Tridentine rite of the Mass due to its excesses. Disputes also arose in the doctrinal sphere. Following the publication of Amoris Laetitia in 2016, a small group of cardinals (Raymond Burke of the United States; Walter Brandmüller of Germany; Joachim Meisner of Germany; and Carlo Caffarra of Italy) presented the Pope with a set of doubts, or dubia, regarding the provisions on communion for divorced and civilly remarried Catholics. Then, in 2023, five cardinals (Raymond Burke, Walter Brandmüller, Joseph Zen Ze-kiun of China; Juan Sandoval Íñiguez of Mexico; and Robert Sarah of Guinea-Conakry) again sent a set of dubia in a letter to the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith, with questions regarding the Synod of Synodality. The Vatican released Pope Francis’s complete response on October 2. Cardinal Raymond Burke, a symbolic leader of the fundamentalist wing, was removed from the Apostolic Signatura in 2014. Francis stripped him of certain privileges in 2023. During COVID-19, he became known for his denialist theories about the pandemic, was critical of social distancing measures, and spoke publicly against vaccines.

9. Social Teaching

Francis’s teaching on social matters was marked by an insistent search to give a voice to those without a voice, to integrate, to engage in dialogue, and to leave no one behind, as well as his constant attention to the peripheries. Through this teaching, he sought to promote a culture of encounter and condemn what he called the “throwaway culture,” which he observed reflected in various aspects of culture and society.

For the Pope, social and political life cannot exist without conflict; poverty, injustice, corruption, violence, and disagreements are present. In Evangelii Gaudium, he proposed that when faced with conflict, three different attitudes are possible: ignoring it, pretending it doesn’t exist, remaining trapped in it, losing perspective, interpreting everything in terms of conflict, and projecting all the evils onto institutions; or embracing conflict, that is, “accepting to suffer conflict, resolve it, and transform it into a link in a new process.” To this end, he insisted on embracing human dignity in all, that dignity that is infinite, sacred, and inviolable. The document Dignitas Infinita, a Declaration published by the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith in 2024 on the 75th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, is relevant here. Dignitas Infinita denounces thirteen grave situations that threaten human dignity in today’s world and that have been attacked on several occasions by Francis: the drama of poverty, the catastrophe of war, labor exploitation, human trafficking, sexual abuse and violence against women, abortion, euthanasia and assisted suicide, surrogacy, the discarding of people with disabilities, racial and ethnic discrimination, violence against people based on their sexual orientation, the use of technologies that degrade the dignity and the culture of waste, of the weak, the elderly, the sick, the poor, and migrants. Human dignity is presented here as an essential condition for elaborating and constructing fundamental rights and communion across differences. It is impossible to resolve conflict without first assuming this basic presupposition: the inherent dignity of all human beings.

Following the same line as his predecessor, Benedict XVI, Francis insisted on the primacy of politics over economics. Fratelli Tutti emphasized that economics must be integrated into the political project, rather than the other way around; the dimension of what is possible and available must be guided by the dimension of what is desirable about the proposed ends. Thus, he insisted that “politics must not be subject to economics, and the latter must not be subject to the dictates and efficiency paradigm of technocracy” [7] but rather, “we urgently need politics and economics, in dialogue, to place themselves decisively at the service of life, especially human life” [8]. An economy oriented toward the future can escape the obsession with immediate results and join the path of common objectives.

He was also a critic of ideologies, fully embracing the principle he proposed in Evangelii Gaudium: “Reality is more important than the idea.” Reality exists; the idea is developed, and when it is separated from reality, it becomes ideology —the fruit of idealism and nominalism. This is where one of Francis’s most persistent criticisms of the technocratic paradigm comes in: the tendency to prioritize technical and efficiency arguments instead of considering anthropological and human issues. In Fratelli Tutti, he spoke of various “closed and monochromatic economic visions,” such as theories of infinite growth on a finite planet, trickle-down economics, absolute reliance on markets and their ability to self-regulate, which makes them incapable of solving social and environmental problems; extreme meritocracy, which ignores structural inequalities and fosters a throwaway culture; or the financialization of the economy, that is, an economy based on the flow of capital and financial speculation, which disconnects money from production and labor. The Pope called for a return to reality, especially for the poor who can no longer wait. The mere idea makes them invisible and functional.

The encyclical Dilexit nos, although not strictly a social encyclical, provides a foundation for concern for all things human because Christ loves them. For this reason, the Pope affirmed that Dilexit nos “allows us to discover that what is written in Laudato Si’ and Fratelli Tutti is not foreign to our encounter with the love of Jesus Christ, since by drawing from that love we become capable of forging fraternal bonds, of recognizing the dignity of every human being, and of caring together for our typical home.” For this reason, this latest encyclical is understood as the interpretive key to the entire pontificate, especially in social matters, where the solution to social and environmental problems, economic imbalances, or the inhumane use of technology, lies in recovering one’s heart in being moved, in going beyond oneself; in looking upward, reaching out, initiating processes, aiming for a more perfect and more integrative whole.

10. Mercy and Hope

Mercy and hope are two realities that Francis wished to emphasize with particular force during his pontificate. It is not without reason that the two jubilees he proclaimed were dedicated to these two virtues.

By calling 2016 for an extraordinary jubilee dedicated to mercy, the Pope sought to highlight the most beautiful face of the Church: one that, following the example of the Good Samaritan, becomes a “field hospital” to heal the wounds of those left by the wayside. The expression “field hospital” was used by Francis in an interview with Antonio Spadaro and published by La Civiltá Cattolica shortly after the beginning of his pontificate in September 2013, where he stated: “What the Church needs most today is the ability to heal wounds and warm the hearts of the faithful, closeness, proximity. I see the Church as a field hospital after a battle.” For the Holy Father, mercy is “the greatest of all the virtues” [9], and the Church is called to be “the place of gratuitous mercy, where everyone can feel welcomed, loved, forgiven and encouraged to live according to the good life of the Gospel” [10]. With these affirmations of Evangelii Gaudium, the Pope made clear where his pastoral emphasis would lie: on being missionaries, reaching out to others, and going to the peripheries. With the Holy Year of Mercy, the Pope invited the Church to rediscover the merciful face of God, opening holy doors in prisons, hospitals, and refugee camps. In the Bull of Invocation for that Jubilee, the Pope affirmed that “Jesus Christ is the face of the Father’s mercy. The mystery of the Christian Faith seems to find its synthesis in this word,” [11], and then defines mercy: “It is the way that unites God and man because it opens the heart to the hope of being loved forever despite the limits of our sin.” Thus, God’s mercy should not be an abstract idea, but a concrete reality through which He reveals His love like that of a father or mother deeply moved by their child.” [13] At the end of his pontificate, he later sought to recall this same centrality of mercy with the encyclical Dilexit Nos, an encyclical entirely dedicated to the heart of Christ from which mercy springs.

In 2025, as is the Church’s tradition every 25 years, the Pope proclaimed a new Jubilee, this time dedicated to hope. Hope was the gift the Pope invoked for the Jubilee Year, inviting the faithful to be signs of hope amid the various storms humanity is experiencing. He had already forcefully proclaimed this gift in Evangelii Gaudium, where he stated: “Let us not allow hope to be stolen from us!” [14] and “Let us not remain on the sidelines of this march of living hope!” [15] Because Christians, despite everything, despite wars, poverty, and suffering, keep alive their hope, which “is born of love and is founded on the love that springs from the Heart of Jesus pierced on the Cross.” [16] For Christians, there is always hope, even in the darkest moments; as he recalled in the historic Urbi et Orbi blessing of March 27, 2020, amid the pandemic, “Do not leave us at the mercy of the storm. Amid our darkness, You shine.” Or in Laudato si’ where, after describing a bleak panorama, he affirmed that hope “invites us to recognize that there is always a way out, that we can always redirect our course, that we can always do something to solve problems” [17], or in Fratelli tutti where he invited us to walk in hope, that hope that can shine independently of circumstances or historical conditioning, for hope “knows how to look beyond personal comfort, beyond the small securities and compensations that narrow the horizon, to open itself to great ideals that make life more beautiful and dignified.” Hope [18] is missionary; it is dynamic and a force that impels us to go forth. And, as he noted when announcing the Holy Year 2025, “hope does not disappoint because it is founded on the love of God, a love that transforms even the darkest moments into opportunities for grace” [19].

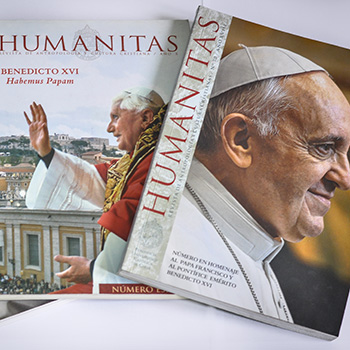

You can learn more about Humanitas magazine by clicking here (in spanish).

Archivo histórico de todas las revistas publicadas por Humanitas a la fecha, incluyendo el número especial de Grandes textos de Humanitas.

Archivo histórico de todas las revistas publicadas por Humanitas a la fecha, incluyendo el número especial de Grandes textos de Humanitas.

Algunos de los cuadernos más relevantes que ha publicado Humanitas pueden encontrarse en esta sección.

Algunos de los cuadernos más relevantes que ha publicado Humanitas pueden encontrarse en esta sección.

Reseñas bibliográficas de libros destacados por Humanitas.

Reseñas bibliográficas de libros destacados por Humanitas.

Tenemos varios tipos de suscripciones disponibles:

-Suscripción anual Chile

-Suscripción anual América del Sur

-Suscripción anual resto del mundo

Suscripción impresa y digital de la revista Humanitas

Tenemos varios tipos de suscripciones disponibles:

-Suscripción anual Chile

-Suscripción anual América del Sur

-Suscripción anual resto del mundo

Suscripción impresa y digital de la revista Humanitas

Seguimos y recopilamos semana a semana todos los mensajes del Papa:

-Homilías de Santa Marta

-Audiencia de los miércoles

-Encíclicas y Exhortaciones

-Mensajes

Seguimos y recopilamos semana a semana todos los mensajes del Papa:

-Homilías de Santa Marta

-Audiencia de los miércoles

-Encíclicas y Exhortaciones

-Mensajes

Desde el año 2003 revista HUMANITAS publica todos los viernes estas páginas en el Diario Financiero. A solicitud de los usuarios de nuestro sitio web, ponemos a su disposición los PDFs de los artículos más recientes.

Desde el año 2003 revista HUMANITAS publica todos los viernes estas páginas en el Diario Financiero. A solicitud de los usuarios de nuestro sitio web, ponemos a su disposición los PDFs de los artículos más recientes.